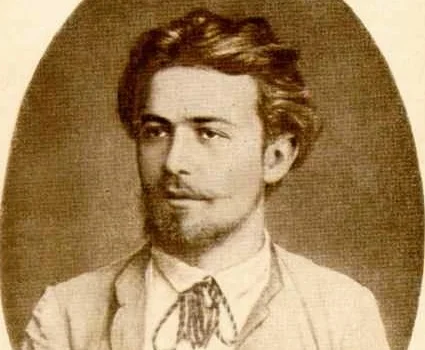

“[H]e was tall, slim, very good-looking, he had dark reddish waving hair, a little graying, he had slightly clouded eyes that laughed subtly, and a fetching smile. His voice was pleasant and soft and, with a barely perceptible smile.” —Anna Suvorina

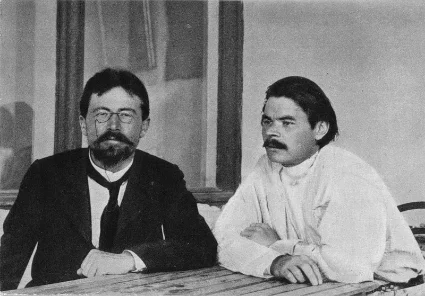

By all accounts, Anton Chekhov was a charming, tactful and dignified man. A subtle smile and calm demeanor greeted those who met him and those who knew him well. He had a magnetic effect on the people he encountered. This was partly his personal charisma and partly a tempered sincerity in his conversation. His younger contemporary Maxim Gorky described this in his slightly-deifying account:

“That was a characteristic of him, to speak so earnestly, with such warmth and sincerity, and then suddenly to laugh at himself and his speech. In that sad and gentle smile one felt the subtle skepticism of the man who knows the value of words and dreams; and there also flashed in the smile a lovable modesty and delicate sensitiveness… in Anton Chekhov’s presence every one involuntarily felt in himself a desire to be simpler, more truthful, more one’s self.”

Indeed his personal magnetism was a bit unwieldy. In his prime, he seems to have attracted nearly every woman he encountered, while he himself was distinctly and destructively noncommittal in such affairs. Laden with a throng of dependents and with dueling careers of medicine and literature, Anton Chekhov had little room for the demands of marriage until the end of his life was in sight.

Reading about his life, one is struck by the full and engaged life he lived, despite not having children and dying at the age of 44. That life involved sacrifice and profound levels of exertion and productivity—as a doctor, a writer, a provider and a philanthropist. This is the kind of workload mirrored in Lopakhin, his high-reaching character from The Cherry Orchard. This was the serf’s internalized work ethic, to which so many characters allude in his writing.

Anton Chekhov with Maxim Gorky in Yalta, Sept. 1899

Gorky also speaks of Chekhov’s passion for education as the solution to his country’s deep problems. Young Anton had lifted himself from the lowest rung of the merchant class and reshaped his destiny through education, through schools and libraries. And throughout his adult life, he gave back by building and supporting schools and libraries wherever he lived and in places where he heard of the need. So open of hand was he that he always teetered on the border of insolvency, despite his preeminence as Russia’s most popular writer for well over a decade. Like a fountain, he constantly emptied himself and was replenished, whether with money, with stories, with ideas or with cares.

Anton Chekhov—it should be said—was not flawless. His moral character was quite complex, as one who has carefully read his work might intuit. In an iconoclastic 1998 biography, Donald Rayfield dug deeper into the details of Chekhov’s life and relationships than any previous attempt and convincingly overturned the highly-curated version of Chekhov’s life passed down through most of the 20th Century. A close-up view of Chekhov’s interactions with family, friends and associates reveals some less attractive traits of ambition, callousness, impulsivity and despairing.

We should all fear such a close-up view—we all who honor the Golden Rule. Perhaps though to dispel a myth, it is valuable, and how much moreso if we can better understand his art. In Rayfield’s words, if “the man that emerges is less of a saint, less in command of his fate than we have hitherto seen him, he is as much a genius and no less admirable.”

Next time we’ll look at Chekhov’s childhood and youth and see what pearls we can discover from the Sea of Azov, where he was born and grew in the port city of Taganrog.

To judge a work of art, one need not investigate the life of its maker. Art exists on its own, to be judged by rules of form, aesthetics, etc. Indeed beautiful art has been made by ugly personalities throughout history, and vice versa. But it would be hard to argue there is no correlation between creator and created. This is especially the case when we look at drama, that most human-focused of arts. So often we see how a play's themes, characters and stories reflect the life, the passions and the preoccupations of the playwright. At the most fundamental level, a playwright's character and values—whether acknowledged or not—bleed into the work and into its dramatic premises and assumptions. When it comes to great art and difficult art and groundbreaking art, it's especially useful to look into the artist's life. All three of these designations apply to the plays of Anton Chekhov

In those plays, characters vibrate with quirk and complexity, dialogue meanders and erupts while plots move tectonically, and yet rarefied moments open up in which we glimpse, as Andrey Bely phrased it, "an opening into eternity." Unlike almost any other playwright, Chekhov opened up a genre that is virtually entirely his own. His plays, according to scholar Laurence Senelick, “derived from no obvious forerunners and produced no successful imitators.” Chekhovian drama is part Realism, part Farce, part Symbolism, but in what proportion? From the very first, directors have scratched their heads trying to get the formulation right. A look at his life, his influences, his work and a century-plus of criticism will get us closer to that magic formulation.