“What writers of the gentry had free from birth, we the underclass have to pay for with our youth.” (Anton Chekhov, Letter to A. Suvorin, Jan. 1889)

Most of the great Russian writers of the 19th Century—Pushkin, Lermontov, Gogol, Turgenev, Dostoyevsky, and Tolstoy, to name the most prominent examples—came from the Russian aristocracy or the landowning class. Not so Anton Chekhov. Most of his ancestors were serfs—slaves, that is, lest we interpret the word euphemistically.

His paternal grandfather, Egor Chekhov, had earned money to buy freedom for himself and his dependents in 1841, while his maternal grandfather, Iakov Morozov, had been freed by his father’s labor in 1821. Only Anton’s maternal grandmother, Aleksandra Kokhmakova, had come from affluence—still non-gentry, but they were respected craftspeople. By 1860, when Anton was born in the port city of Taganrog, his family were considered meschchane, or petite-bourgeoisie—a class hovering above servitude.

The port city of Taganrog, the birthplace of Anton Chekhov .

While 19th Century Russia’s class system was highly regimented and codified from the Tsar on his throne to the peasant in the field, it was also increasingly porous. Social reforms of the 1860s brought new possibilities to millions—the most sweeping of these reforms was the general emancipation of serfs in 1861. Social mobility was possible, and education was key. And despite the numerous dreadful remnants of serfdom that remained in their blood, the Chekhov family kept sight of the value of education as a means of social uplift.

The life of the Chekhovs in Taganrog was marked by cramped quarters, chaotic finances and emotional hardship, constant moving from one house to another. There were always relatives and other stragglers living with them, swelling the number of dependents. The house was tyrannically run, and yet somehow they maintained their cohesion. Together with their extended family, they were considered clannish by townspeople.

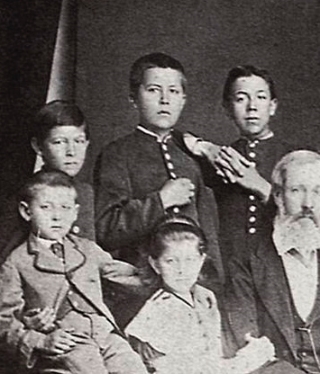

The Chekhov family--parents and six children--with other relatives, 1874. Anton stands second from left. His father and mother are seated center.

Anton’s father, Pavel Egorovich Chekhov, was a shopkeeper selling various household goods. The store was never run right as Pavel was more interested in conducting church choir than serving customers. He was a complicated case: religious, drawn to the arts, dedicated to family, and yet abusive in the extreme during the childhood of Anton and his brothers. He beat them mercilessly, considering it his God-given duty.

The two older boys—Aleksander and Kolia—were traumatized by this abuse. Both wet their beds well into their teens. Despite remarkable talents and ample opportunities, both displayed self-sabotaging behavior that kept them from stability or success whether with career or family. As an adult, Anton wrote to Aleksander, “Tyranny and lies crippled our childhood so much that it makes me sick and afraid to remember.” This note of commiseration notwithstanding, Anton seems to have responded differently to the tribulation. He grew tougher.

Pavel himself was thrashed as a child by his father so badly that he had to wear a truss his entire life. In fact, in 1898 at the age of 73, he decided one day not to wear his truss and he died as a result of the complications arising. His son was not present to treat him.

Anton’s mother, Evgenia Morozova Chekhova, was kind-hearted and comely. She had no dowry, so she married a man below her inherent quality. She gave birth to seven living children. Six of her children—five boys and one girl—grew to adulthood: Aleksander (b. 1855), Kolia (b. 1858), Anton (b. 1860), Vania (b. 1861), Masha (b. 1863), and Misha (b. 1865). She was devastated by the loss of the last one, a baby girl named Evgenia, when Anton was 11.

Throughout his life, Anton cared deeply for his mother, while he showed only filial respect for his father. He faulted him for the abuse and humiliation his siblings and his mother experienced. At the same time, Chekhov would spend most of his life surrounded by and providing for both his parents. At the age of 17, during a lengthy period of separation from them, he wrote to a family member:

“My father and mother are the only people in the whole wide world for whom I shall never ever grudge anything. If I ever stand high, it is their doing, they are glorious people, and their unbounded love of their children puts them above all praise, compensates for any faults of theirs.”

Looking over their lives, one sees that Chekhov’s family members—immediate and extended—were dealt an extra portion of talent and yet a general inability to control it or benefit from it. They were something like the dramatis personae in his plays, a cast of well-meaning, passionate, caring, inept, hypocritical, delusional individuals who love each other but can’t stand to be either with or away from each other.

As a student, Anton was rather unremarkable at first. For one thing, he was forced to spend long hours even at a young age watching over the shop while his father pursued his interests elsewhere. He and his brothers were pushed to sing choir music until they grew hoarse. Still he made his way through the Taganrog school that thrived in the period he and his siblings attended. According to Donald Rayfield,

“The quiet resistance to all authority, the core of Anton’s adult personality, was fomented in the classroom. The gimnazia was a great leveler—upwards, rather than downwards. It gave pupils from poor, clerical, Jewish or merchant households the rights and aspirations of the ruling class.”

Everything changed when Anton was 16, when his family began their protracted move to Moscow—his brothers as students, his father as a fugitive from debtors. Anton was put in charge of the store, as well as the family’s property and financial affairs in Taganrog. It would be three years that he would be separated from them, three years of difficulty and growth, three years of turning towards and yearning for Moscow.

At this point, something in his character shifted. He began to excel at his studies. Maybe it was the solitude, or the ability to concentrate in a more stable living environment with family friend Gavriil Selivanov—a prototype of the character Lopakhin. He began to seriously consider medicine as a career. More than this, he gained an independent drive and purpose and work ethic that would carry him the rest of his life.

The secret to Chekhov’s worldly success you can see lay not simply in talent or genius, but in that chip of hardness, the callousness to make his way in the world, to calculate and make cold, rational decisions. This quality clashed with his dominant bearing of tact and mannered wit, and it was a recurrent confoundment for all who let him into their hearts—from his brothers to his collaborators to his lovers to literary statesmen, all experienced one time or another the flint in his character.

Anton Chekhov, painted by his brother Kolia, 1884

In 1879, Chekhov closed up shop for good in Taganrog and headed to Moscow, to stay with his struggling family and to join Moscow University’s medical faculty—that is, to start five years of medical training. There, he would begin writing parodies for small periodicals to print at 5 kopecks a line as a way of supporting his large family. This would open the door to writing short stories, all the while studying and beginning his medical career, all the while helping to manage a bustling household.

Short stories would be his ticket to the elite circle of Russian literary figures. He would come to write some longer pieces—novella size, but never anything on the door-stopping scale of Dostoyevsky or Tolstoy, whose works are infamous for their length and depth, import and sermonizing. Chekhov never had the psychological space afforded him to develop story on such a scale. Most of his early stories, he claimed, he tossed off in 24 hours or less. Chekhov took to writing not to change the world but to provide for himself and his large family. As was quoted at the beginning, he paid with his youth “what writers of the gentry had free from birth.”

That quote, from a letter to his friend and publisher A. Suvorin, continues in a most instructive way showing how a 29-year old Chekhov saw his own upbringing and framed his process of refining his character. He wrote it, however, as if sketching out a character study for a short story:

“Why don’t you write the story of a young man, the son of a serf, a former shop boy, chorister, schoolboy and student, brought up on deferring to rank, on kissing priests’ hands, submitting to others’ ideas, thankful for every crust, thrashed many times, who tormented animals, who loved having dinner with rich relatives, who was quite needlessly hypocritical before God and people, just because he knew he was a nonentity—write about this young man squeezing drop by drop the slave out of himself and waking one fine morning feeling that real human blood, not a slave’s, is flowing in his veins.”

MP

Most of the information included here comes from the Donald Rayfield biography, Anton Chekhov: A Life. See my review: