Who's afraid of Alice Childress?

(Notes for the 2015 Playmakers Production of Trouble in Mind by Alice Childress)

by Mark Perry

“Trouble in Mind… Now what's that about?” Some of our patrons may have wondered this when first hearing the title in Playmakers current season. It is a lesser-known masterwork of a slightly better-known author, Alice Childress (1916-1994). Childress probably reached her widest audience with the 1973 novel and 1978 film of "A Hero Ain't Nothin but a Sandwich." This play though seems to be enjoying a revival in the 21st century. It's funny, fresh, profound, and surprisingly timely for a play written two years before the first Edsel rolled off the showroom floor and into comic history. Assuming there isn’t just one spot in our dramatic canon for an African-American female writer before 1975, why isn't this play included in our drama anthologies, say, between "Cat on a Hot Tin Roof" and “J.B.”? Part of the answer may be found in the play’s production history.

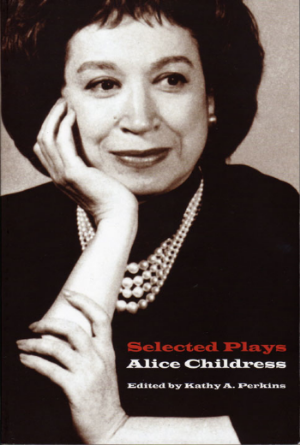

Given the cultural environment of the 1950s, the play was a breakthrough for its time. It opened on November 3, 1955 at the Greenwich Mews Theatre, a 200-seat Off-Broadway house and played for 91 shows. This was a first for the race, so to speak—the first mainstream, professionally produced play (that is, with unionized actors) by an African-American female playwright. Other firsts had preceded this one and still others would succeed it, but this was a big deal. Not so interested in such designations, Alice Childress just wanted her plays to be done and done truthfully. Concerned about deep-seated stereotyping, she directed this production herself. Ah, but there was a problem, said the producers: the ending. Audiences—white audiences, that was—weren't going to like this unsettling ending. In a bewildering case, as Childress anthologist and friend Kathy Perkins notes, of life imitating art that one can only appreciate after seeing the play, here was this dispute between the cautious white producers and the righteous black female asserting the need for a truthful ending. She compromised and wrote a happier ending for the production. As was bound to happen, The New York Times review came out with strong praise for the play, all except for the ending. The play had been optioned for Broadway, and Childress struggled to revise, but ultimately negotiations broke down. Burned by the experience, she vowed never again to cave artistically to producer pressure. She went back to her original ending, but had lost some steam in promoting the play in the process. As a result, the first Broadway play by an African-American female would be 1959’s “A Raisin in the Sun” by Lorraine Hansberry.

Photo from 1955 New York Times Review

Mind you, African-Americans had long performed on Broadway—acting, dancing and singing. “Trouble in Mind” takes us into the first week of rehearsal of just such a Broadway play called “Chaos in Belleville,” a melodrama about a Southern lynching. We meet Wiletta, the lead actress in the play, middle-aged and still enamored of the stage life. The company is interracial, and they generally consider themselves more sophisticated than the Southerners they are portraying. And they are certainly more sophisticated than the painfully-stereotyped caricatures provided them by the absent white author. While “Chaos in Belleville” is a satirical creation of Childress, it is close to the mark for what constituted mainstream entertainment in the first half of the 20th Century. The African-American actors here are quite accustomed to playing such derogated projections of their kind. They accept it though for need of work and for love of performing. As Wiletta says, “it’s the man’s play, the man’s money and the man’s theater, so what you gonna do?” Even today, this predicament of power persists, leading, as Kathy Perkins says, to people of color “still being portrayed stereotypically on both stage and film or just being erased out of history as in the current film Exodus.”

Now our play-within-a-play is not without its virtues. It is well-intended with an anti-lynching theme, a genre that both white and black playwrights had actively embraced since the first part of the 20th Century. All people of goodwill could rally against such domestic terrorism. Our very own progressive-minded Paul Green wrote many such “Negro dramas” with sympathetic portrayals of African-American characters, most famously his Pulitzer-Prize winning “In Abraham’s Bosom” (1927). More importantly though, in our consideration of Alice Childress’s development, is the history of African-American playwrights emerging in the 1910s, 1920s, and 1930s, especially in Harlem and Washington DC. These women and men, such as Angelina Grimke, Willis Richardson, Georgia Douglas Johnson, Langston Hughes and Eulalie Spence, contributed to a growing stream of noteworthy dramatic writing, responding to such calls as W.E.B. DuBois’s famous manifesto seeking plays “about us, by us, for us, near us” and Alain Locke’s cultivation of Negro folk drama at Howard University. Works by these playwrights, as well as by Green and others, would be performed by thousands of amateur Negro theatre groups founded in schools, clubs and communities around the country in the times before the Great Depression dried up much of that stream.

The Group Theatre’s 1931 production of Paul Green’s ‘House of Connelly.’ (Paul Green Foundation)

There is, of course, an irony in an anti-lynching play that ends in a lynching, as so many of them did. While the playwright may believe this enactment is necessary to stir the sympathy of the audience and get them to react to the seriousness of the matter, the psychological and emotional effect of repeated exposure on the audience may be counterproductive. We as audience often feel an inevitability about actions that we watch dramatized, as if Fate has determined the course of these things in its relentless way. Before Fate, we are all victims. Hearing stories of lynching spoken aloud, reading about them in the papers, seeing the pictures, then watching the same enacted, we enter a cycle in which that narrative feels fated. Lynching is inevitable, says the tape recorder in our brain—the tape recorder over which our internal stage manager has little control.

Now Wiletta does not come to the “Belleville” script with any such finessed dramaturgical considerations. Her words are more to the point: “It stinks.” That said, her finesse is found in the shield she carries to guard herself from any such psychological and emotional impact. Upon meeting the neophyte John, Wiletta shares the wisdom of her trade, introducing point-by-point a system of working in the white-dominated world of the professional theatre, what we might call code switching and what John dares to call “Tomming.” There is a face and attitude and speech one has towards whites and the white establishment, and there is a face and attitude and speech one has with the black community. There is the Mask, the Front, the Show put on for the Other, and then there is the natural feeling of being with one’s own. In virtually all plays, we gain dramatic irony by seeing more than some of the characters see. Here, Childress provides early-on a concise glossary of African-American code-switching—a code we still recognize, and therefore allows audience members of all colors to participate in the play’s dramatic irony for purposes both comic and serious.

If we look more deeply, we see this Masking, this hypokrisis or putting on of a show, has its origins in the painful crises of history. From the word GO, slavery and performance were linked. African slaves were forced to dance and sing aboard the ships in the Middle Passage, and again at auction, and then perpetually for the owners’ entertainment. Perhaps more insidiously, slave masters would force slaves to pretend to be happy and content with their lot when in public or otherwise in the presence of whites. So this Masking, this pretense to pleasantry, comes from a deep and dark place. And yet performance—singing, dancing, enactment—was also a source of life and light in lives otherwise hauntingly bleak. The songs of slaves, rooted in African melody, expressed both sorrow and objection—such “wild songs” abolitionist Frederick Douglass said animated his desire for freedom. We hear their echoes down into the songs in “Chaos in Belleville” even. What a complicated picture the double consciousness of performance! As Douglas Jones of Rutgers says, “Since performance sustained slavery and freedom, it could not be trusted nor neglected.

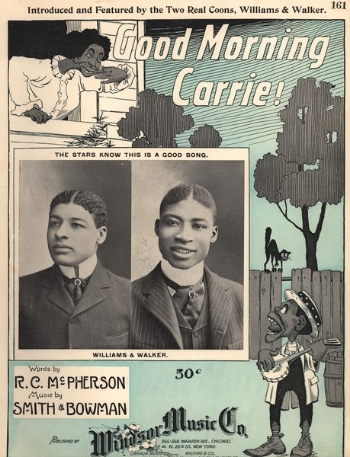

1901 Sheet music showing both performer dignity and stereotyped roles

Also originating in the painful crucible of enslavement is another prominent feature of Childress’s world here, and the other side of the Masking described above: the collectivism and group identity of the African-American community. Once in captivity, differing African nationalities quickly merged together into an identity defined by “blackness.” Even in “Chaos in Belleville’s” newly-formed interracial theatre cast, a black collective is immediately assumed, and no sooner assembled than it is challenged. Jealousy, ambition, narcissism—behaviors frequently reflected in the mainstream American theatre community—do their damage, but the appeal of interracial mingling is also a test. Finally, what happens to a collective when the individual is impelled to arise in an act of conscience that the group would otherwise stifle?

This will be Wiletta’s trial. While she begins the play with no qualms of conscience and no intention of letting down the Mask, her inherent dignity gets the better of her. Her awareness piqued by an acting exercise, she has trouble in mind over a plot that makes no sense and characters whose motivations are irrational. The truth is the writer is unwilling to attribute any agency or any heroic virtue beyond victimhood to African-American characters. She brings this up with Al Manners, the mercurial director who presses the behavioral code of the theatre: Actors do not change the script; they need not worry about the narrative, just to learn it word-perfect and perform it.

To be plain, the subtext not only of “Chaos in Belleville” but of the rehearsal room is the same exploitative, dehumanizing narrative that serviced the enslavement of the African people in America by the whites: “You don’t have any power. We have the power. Give up, don’t think, don’t question. Or else…” Watching the play from this perspective, one begins to experience synaptic fireworks, marvelous connections this underappreciated playwright made as she realized the dream voiced by Wiletta: “I’ve always wanted to do somethin’ real grand… in the theater.”

The playwright, herself light-skinned and somewhat uneasy about it, stood at an intriguing threshold—one that may have proved too challenging for audiences of its time. This was not a theater that compromised and showed white projections of blackness, nor was this a theater “about us, by us, for us…" This was a theater about encountering “them,” and in several of her most well-known plays, she is relentless about this. These encounters are explosive, and they signal, at best, mindlessness and, at worst, malicious bigotry on the part of the white characters, who stand in positions of relative authority, towards the black female characters, who are distinguished in each case by a deteriorating capacity to hush up, nod and play along. The dynamic of racial interaction she shows is scary and uncertain as to outcome, but the necessity is unrelenting. Pressure is building. What happens to a dialogue deferred?

So who is afraid of Alice Childress, our Leftist, Feminist, Black Nationalist and Liberationist playwright? Only those whose privilege blinds them to the radical truth spoken of by the Psalmist and recited by Wiletta at the play’s end: “Behold how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity.”

For an excellent resource, see Selected Plays by Alice Childress. (Kathy A. Perkins, editor. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2011.)