Salem, McCarthy, and the Spectre of Mass Hysteria

(Notes for the November 2016 PlayMakers Production of The Crucible by Arthur Miller)

by Mark Perry

In a 1960 interview, playwright Arthur Miller described his motive in writing “The Crucible” as follows:

It was an attempt ... to say that one couldn't passively sit back and watch the world being destroyed under him, even if he did share the general guilt ... I was calling for an act of will. I was trying to say that injustice has features ...

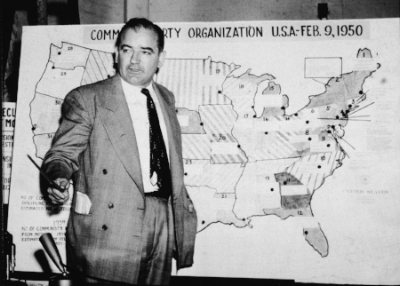

The immediate injustice he was responding to when he wrote the play in 1952 was the Red Scare[1], the rampant spread of anti-Communist sentiment as the U.S. entered into a Cold War with Russia. Senator Joseph McCarthy became the most prominent prosecutor of the witch-hunt that sought out any communists or sympathizers in government or indeed at any level of public life. This wreaked havoc in Washington, but also in Hollywood and in New York.

Regarding McCarthy, Arthur Miller later said, “[J]ust about anything that flew out of his mouth, no matter how outrageously and obviously idiotic, could be made to land in an audience and stir people’s terrors."

Miller would himself be investigated in 1956 and called before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), where he testified honorably and did not name names when prompted. The tide eventually turned, and both McCarthy and McCarthyism would be discredited, with the Senator dying of acute hepatitis in May 1957.

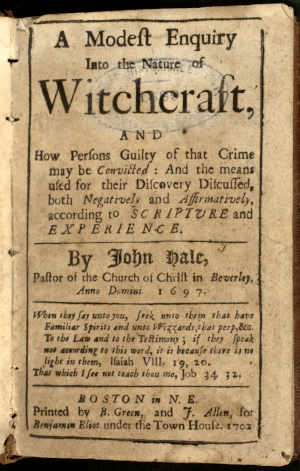

One might guess that what attracted the playwright to the story of Salem, the archetypal witch-hunt in American history, was the desire to find an historical analogue with which to compare the current crisis. This is partly true, but Miller had always been fascinated by the history at Salem. He was drawn to “the interior psychological question … of that guilt residing in Salem which the hysteria merely unleashed, but did not create.”

In the Spring of 1952, Arthur Miller traveled to Salem to learn about and viscerally connect to the truth of the story he wished to tell. For days on end, he sat in the courthouse reading the old transcripts of the trial. That world came alive to him—its people, he said, becoming "more real to me then the living can ever be." He experienced "a feeling of love at seeing Rebecca Nurse's house on its gentle knoll." It was this connection to the source material that made the play so personal to him. Despite its remote subject matter, he would later remember it as the play of which he was most proud.

Salem

As a child growing up in southern New Hampshire, I went on school field trips to Salem. The exhibitions emphasized the dim, colorless lifestyle of the Puritan. I remember the hysterical screaming of the young bewitched girls and the stupidity of the superstitious elders in responding to these ravings. These presentations were always kind of campy, as is inevitable when mannequins stand in for real people. The edge of the horror is dulled.

Today, Salem is known as "Witch City." It has rows of storefronts that are witch- and magic-themed. The police cars have cute little witch silhouettes detailed on them. There is even a statue of Elizabeth Montgomery, the star of the 1960’s camp comedy, "Bewitched.” She sits astride a broomstick nearby a crescent moon—a cute and kitschy magnet for selfie-seeking tourists.

Salem also provides museums, landmarks, historical sites and other research opportunities for the serious historian and the merely curious. One fascinating development is that it has become a place of pilgrimage for the Wiccan community. The blood of the innocent sanctified this spot for a small, but vibrant spiritual practice that advocates female empowerment, oneness with the environment and mystical connection between the dead and the living.

One thing you could easily miss in all this: Salem is not Salem Village. Salem Village was the epicenter of the 1692 scourge that struck Essex County and beyond. The evil present in Salem Village does not need a supernatural gloss to understand. It was the deeply-forged discord and factionalism of its residents, which in turn were seized upon by an opportunistic, hate-spouting religious fundamentalism. The spark caught the straw and whooOOSH!! Salem Village is no more. It was dissolved in the early 18th Century into the towns of Danvers and Peabody.

In 1692, Salem Village had perhaps 200 adult community members, living in 85 or so homes scattered about the countryside. It was not incorporated, a jurisdictional extension of Salem Town. The people were largely farmers, and they were notorious in Essex County for their fractiousness. Land disputes were rife, and worsened without a local means of enforcing boundaries. The Village rebelled against Salem Town, which was mainly employed with its port activities. The villagers complained (understandably) about the 7-mile walk to church, and they appealed for their own parish. This was granted, but the community was not satisfied. A climate of discontent among villagers with both outsiders and neighbors had become habitual. They had trouble finding a minister, and in a decade or so, went through three of them. The individuals chosen tended to appeal to one faction and alienate another.

Into this scene walks Samuel Parris (b. 1653), a man who had not succeeded in reaching his life’s ambitions—being a sugar plantation owner in Barbados and a merchant in Boston. He and his wife Elizabeth Eldridge have three children, one of whom is also Elizabeth, known to history as Betty. In 1689, Samuel Parris—now ordained, sets up to minister to Salem Village for the annual salary of 60 pounds plus 6 pounds for firewood. When the majority of the village turned against him two years later, it was this salary they refused to pay in hopes of driving him out. That was in October 1691. If only he had taken his cue and gone out quietly into the night.

But Parris was a fighting man. He had sought to solidify his own position by exploiting divisions present in Salem Village. He preached a divisive gospel — life as a war between God and Satan. Parris pushed hard the separation of the elect church membership from other attendees. Initially this seemed to work, raising membership in the church from 25 to 52 adult members, but he kept pushing. He would not allow communion to non-members, who were only allowed to sit through his fiery sermons and then asked to leave. He would also not allow non-church member infants to be baptized. This incited absenteeism and a backlash. The village committee joined up with non-church members to drive him out that winter: no pay, no wood.

Parris doubled down and attacked his enemies as agents of Satan from the pulpit. He spewed out his venom in apocalyptic terms, dividing the world into the Elect of God present there in the church and the Minions of the Devil outside its doors. There were young, impressionable children sitting and taking in all that venom. Within a couple of months, it had done its work. By January, young girls began to erupt into fits, screaming out in pain and claiming bewitchment. These were the same girls who had heard most persistently and passionately the sermons of Reverend Parris. The first two were his own daughter, 9-year-old Betty, and his niece, 11-year-old Abigail. Soon thereafter, they were joined by the children of Parris’s closest allies.

Whereas Arthur Miller finds motive for the young girls in adolescent rebellion and sexual transgression, today's scholars find more motive in the children simply (albeit histrionically) supporting their parents. This is not to say that the children necessarily acted out of conscious intent. It seems more their actions were the result of the stoking of fears and superstitions in a young and vulnerable psyche until extreme physical and emotional contortions bust out.

Other scholars have put forward other explanations, some of which are quite compelling. These range from the poisoning effect of ergotism to the post traumatic stress disorder associated with the “Indian Wars.” [2]

Watching “The Crucible,” one is struck by its urgency and the sense of anxiety it provokes, as well as the inherent call for justice and restraint. Arthur Miller took some liberties in wrenching a play from this sprawling piece of history. Many of these make good sense, such as the dramatic compression of time and character. Others reflect the predilections of the playwright, such as the invention of a love triangle between one of the accusers and two of the accused—Abigail Williams and John and Elizabeth Proctor.

The historical John Proctor was the sixty-year old tavern owner who brazenly denied the validity of the accusations and violently threatened his servant, Mary Warren, from taking part in the trials. In this man, Arthur Miller found some glimmer of the early-to-mid-20th Century Everyman. And so John Proctor became the decent, but tortured man in the prime of his life, who represents basic nobility and has a fiercely independent sense of what is right. It was through such a character that Miller could stress “individual conscience as the ultimate defense against a tyrannical authority.”

The Salem witch trials left an indelible stain on the conscience of our country. This is despite their being relatively minor in comparison with other atrocities in American history. From beginning to end, the trials resulted in only 25 or so deaths. This is a drop in the bucket when compared with the deaths of the now-almost-forgotten Indian Wars of the time. Still the witch trials have proved a perennial source of fascination and a subject of ready inquiry in times of reflection and self examination.

There is something seminal about them – a fundamental early childhood trauma of the American democratic project. The Puritans, in their fierce drive for independence from English control, were embarking on an experiment in grassroots democracy. The monarch was an ocean away, and the colonists continually put up resistance to autocratic rule. The meetinghouse in each New England town was the center for decision-making, and despite the time’s theocratic impulses, the church itself didn't hold as much power as the community of churchgoers did.

The moral lesson of Salem Village is the danger present in democracy when a community is fractured and estranged, and the leaders who are obligated to heal those divisions instead strive to capitalize on them and thereby hoist themselves into prominence by appealing to the people’s basest fears and superstitions.

Several decades after he premiered “The Crucible”, Arthur Miller marveled at the play’s longevity. Its appeal crossed cultural barriers, and it had indeed become his most produced play—with even more productions than his masterpiece, “Death of a Salesman.” Miller further commented that “it seems to be produced … when a dictatorship is in the offing, or when one has just been overthrown.”

[1] Technically, it was the Second Red Scare—the First Red Scare happening in the late teens and early twenties.

[2] Mary Beth Norton's 2002 work In the Devil's Snare asserts the critical role played by the French-Indian Wars in shaping the people’s susceptibility to mass hysteria. She opens up the world of the trials well beyond Salem village so we sense the debacle not as a local aberration, but as a regional epidemic that involved (directly or indirectly) dozens of communities and Massachusetts Bay Colony’s most powerful individuals. She connects the majority of the actors in the trials—from girls to governors—to the trauma and calamity of the Indian conflicts, mostly in Maine outposts. She concludes that PTSD could well have played a role in the afflicted girls’ responses and that the political leadership (who served as judges) used the opportunity to shift guilt at their own “inadequate defense of the frontier to the demons of the invisible world.” (308)