By Mark Perry

With his 2017 play Everybody, playwright Branden Jacobs-Jenkins has resurrected a 500-year-old morality play and given it a thoroughly modern makeover. The result is entrancing, a standard setter for adaptation, but can a modern morality play hope to save us?

Everybody is a free-form reworking of that highly anthologized, late-medieval gem, Everyman. From the dramatic soil enriched by centuries of Mystery Plays in Western Europe, the morality play sprang up as an effective form for both sermonizing and entertaining.

Allegory and Death

Morality plays adopted the Middle Ages’ penchant for allegory to the purposes of the stage. Audiences enjoyed watching the Christian soul caught between the righteous remonstrations of Virtue and the naughty persuasiveness of Vice.

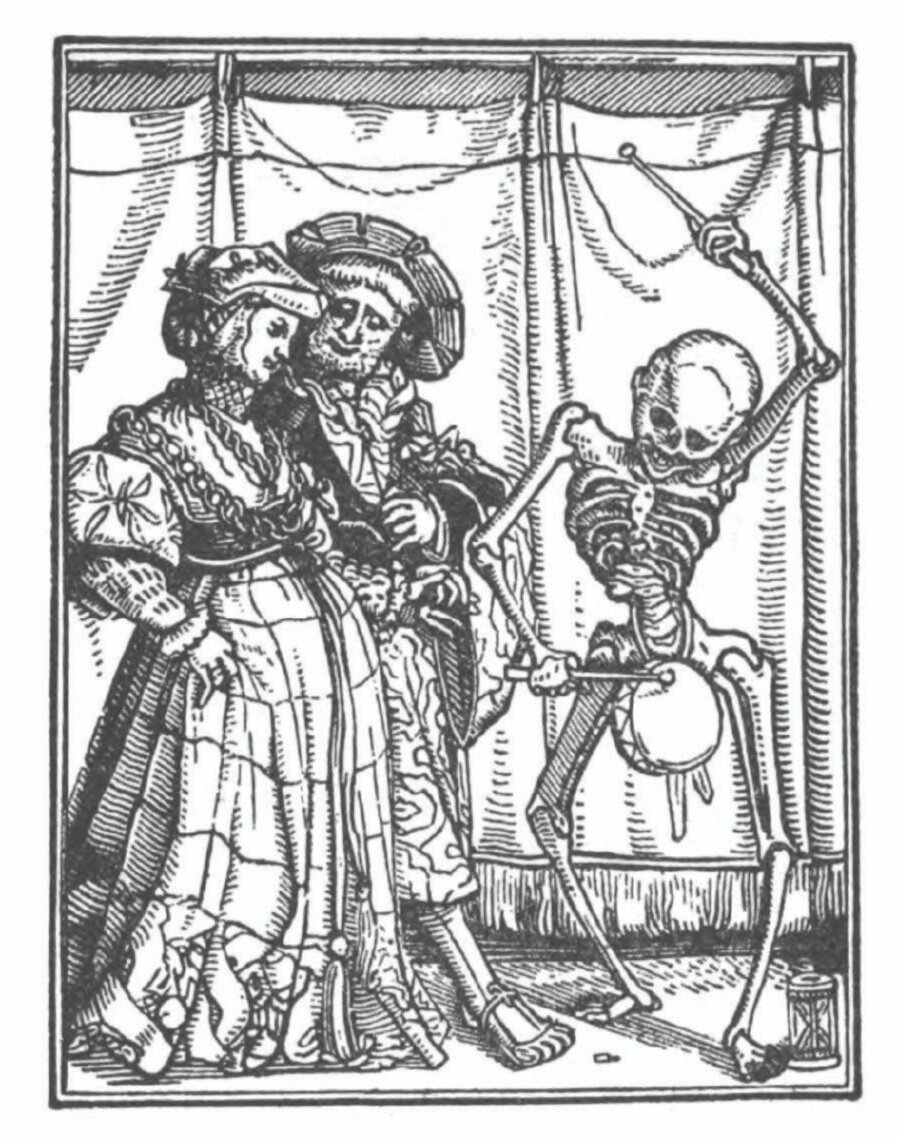

A perennial subject of allegory was, of course, Death. Whether presented as a Reaper, a skull or a skeleton, the various artistic disciplines of the age had their memento mori—that is, their reminders of the inevitable coming of Death. (The dramatic use of allegory would seep into the Renaissance, which turned to Realism without ever surrendering a layer of allegory. We see this in Shakespeare where Vice becomes a template for Iago, just as Yorick’s skull serves to accentuate Hamlet’s encounter with death.)

In the 14th and 15th Centuries, in the wake of the Black Plague and the Hundred Years’ War, the artistic use of the memento mori spread widely. One of its most distinctive expressions was the Danse Macabre. This “Dance of the Dead” first appeared in a popular story, then in the 1400s as a mural on a Parisian Charnel house, portraying skeletons dancing with representatives of all classes of society. A sermon captured in an image, the message was clear: in the face of death, the Pope and the peasant are equal.

“The image tested its onlookers’ immunity to spiritual anxiety.”

“La Danse Macabre” (1485) by Guy Marchant, one of a series of woodcuts based on the murals (1424-5) at the Paris Cemetery of the Holy Innocents.

While the danse macabre was not part of the original Everyman, Branden Jacobs-Jenkins inserts one at the climax of his play with only this description: “SKELETONS dance macabre in a landscape of pure light and sound.”

Everyman

The origins of the English Everyman (c. 1510) are described at some length in Everybody—how it was a close adaptation of the Dutch Elckerlijc (c. 1470), which was in turn based on another story based on a Buddhist tale. (The path from East to West may be traced through the literature of Iran’s Manicheans, Muslims in Baghdad, and Greek-speaking Christians.) That allegorical tale concerned a man who could not find companions for a critical journey from those he loved most (representing wealth and family), but only from one whom he had mostly ignored (that is, good deeds and virtue).

A closer look at Everyman reveals it to be somewhat less medieval and a little more Renaissance than might be imagined. The intended audience was not feudal and agrarian, but city-dwelling. The character Everyman is wealthy, a successful participant in a mercantile economy. This is part of what has made him forgetful and veered him from the straight and narrow.

Theologically, the play is certainly Catholic, and it was not produced in England after the Reformation until 1901. It places some emphasis on methods of confession and penance, but its central theme is more universal: spiritual transcendence is a choice of the individual will, which may be best awakened by reflecting on death.

The journey to Everybody

Everybody strives to bring this theme into our modern world and to amplify its universality in an age of almost unthinkable heterogeneity. The journey to Everybody involved some of what we might expect: name changes, gender adjustments, and a raft of topical references. Fellowship became Friendship, Goods became Stuff, and—in the play’s most inspired doctrinal shift—Good Deeds became Love.

The play’s clever and penetrating language, insistently modern and ironic, engages us and reaches us through the smoke and fire or our near-apocalyptic lives. Characters speak of climate change and foreign labor exploitation. Written by an African American man, the play calls into its vortex discussions of race and identity, but typical flashpoints are used as comic relief rather than points of reflection. The play’s serious dialectical interest is philosophical, timeless, and all-embracing.

Pictures from PlayMakers 2020 Production of “Everybody”

Jacobs-Jenkins had to leave behind the straitened clarity of medieval Catholic doctrine and search for some notion of the mechanics of salvation that might appeal to the broadest cross-section of his intended audience, which, after five hundred years, is still worldly, agnostic city dwellers. The playwright’s answer is not to isolate an answer, but to magnify the question.

He seeks to alienate us—Everybody, that is—from our modern delusions by rattling our metaphysical cages with rapid-fire questioning—an incessant introspection that tag teams with a reflexive ironic detachment. Irony’s relationship with introspection is temperamental. It does manage to cut through the bull, but it may potentially sap introspection of its lasting power. A successful production of the play requires some deliberate evaluation of the layers of emotional truth, illuminating paradox and anxiety-driven delusion voiced by Everybody and company.

“Can you tell me: is this real or is this a dream?”

“This is a theatre.”

Jim Houghton

Everybody revels self-consciously in its theatricality. It is often frivolous and subversive, and it is relentlessly noncommittal. It offers a play within a dream within an allegory within a play. It was lovingly dedicated to Signature Theatre Company’s founding artistic director, Jim Houghton, who passed away in 2016 while the piece was being developed with Signature.

The play’s novel theatrical conceit is that productions use an onstage lottery to choose the actor that is to “die” that performance. In this regard, the play mirrors the indiscriminate manner of Death itself.

The paradox of Salvation

One might argue that an underlying pessimism of the original Everyman does bleed into this adaptation: namely, that people are at best useless and at worst barriers to spiritual transcendence. Human relationships are skewered and held up as flimsy in the face of death. And yet, the only eternal companion we take into death is Good Deeds (in Everyman) and Love (in Everybody), as if those abstractions can exist without family and friendship.

This brings us to the plays’ essential paradox. Salvation may be rooted in individual contrition and surrender, but the expression of that salvation can best be communicated, perhaps only communicated, as part of a communal experience. We are all Everybody, and before Death we are all equal.

“Everybody” is at PlayMakers Repertory Company until Feb 9, 2020. (Link)

From Hans Holbein’s “Pictures of Death” woodcut collection, c. 1523-5